History

As a city, York traces a fascinating history back to Roman and Viking times. Today it has grown to be a bustling commercial, tourist and regional centre. A fine range of restaurants, shopping opportunities and attractions, including the Minster, Jorvik Viking Centre and National Railway Museum, Castle and City Walls. Not forgetting its racecourse.

Horses raced at York during the days of the Emperor Severus in Roman times. However, many of the 360,000 racegoers who will visit the reigning "Northern Racecourse of the Year" this season are unlikely to realise they are taking part in a spectacle that first took place over 2,000 years ago.

York Corporation records show that the City first fully supported racing in 1530. In 1607, racing is known to have taken place on the frozen river Ouse, between Micklegate Tower and Skeldergate Postern.

The first detailed records of a race meeting date from 1709, when much work was done to improve the course at Clifton Ings which was prone to flooding. Despite this work, the flooding continued and in 1730 racing transferred to Knavesmire, where today's course remains.

As its name implies, Knavesmire was common land (open to the knaves), but also a mire with a stream running through it. A considerable amount of levelling and draining was required to create the horseshoe shaped course, which opened for its first meeting in 1731.

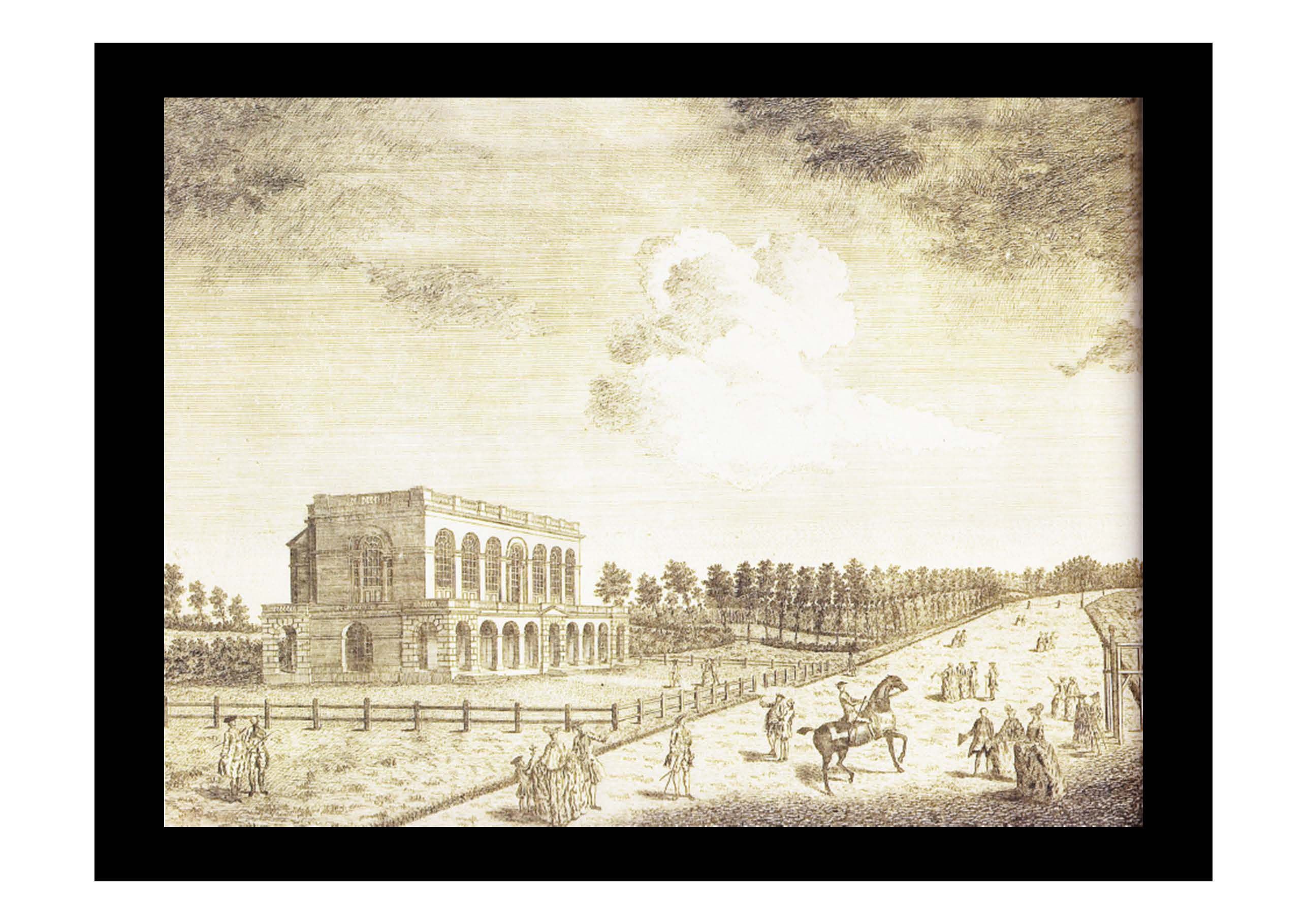

No permanent buildings were erected until the noted York architect, John Carr, designed and built the first Grandstand in 1754. This was financed by 250 people who each paid 5 guineas. Every patron and their successors were entitled to use the stand for the period of the site's lease and were issued with a brass token bearing their name and an image of the stand. This formed the prototype for the late prestigious County Stand Badge.

The design was for an elegant, classical building, two storeys tall with a rooftop viewing platform. On the ground floor, a rusticated arcade led to a hall; above, a reception room extended the length and breadth of the building. From there, racegoers could socialise and watch the races, either from its large arched windows or from the stepped balcony that encircled the first floor.

The Grandstand provided a space in which to both socialise and view the action in comfort, and, through its sophisticated architectural vocabulary, it enunciated the éclat of York races and its patrons. In sharp contrast to the makeshift viewing stands of other courses, it quickly came to be emblematic of the meeting itself and, for the rest of the century, inspired a succession of other grandstands at other racecourses across the country.

Remarkably the heart of the structure is still meeting the needs of modern racegoers, moved eastwards and rebuilt in the early 1900s, it now overlooks the Terrace that recalls its creator, John Carr.

The York Racecourse Committee, (now part of York Racecourse Knavesmire LLP) still manages racing at York today, and was formed in 1842, to turn around a decline in the quality of racing.

By 1846, the Committee had introduced both the Ebor and the Gimcrack Stakes, races which continue to delight the August faithful.

By 1844, the course itself had been made circular, though in search of distance it reverted to an open shepherd’s crook shape for much of the twentieth century, before returning to include a circuit (with chutes) when the North bend was opened in 2004.

An enclosure was built in front of the Grandstand, and a small-scale weighing room was built. A short-lived Stewards’ Stand was erected in 1851, to be replaced by another in 1853, on the north side of the Grandstand.

By 1880, a small polygonal stewards’ stand had been erected between the County and Press stands and, circa 1884, the Half Crown Stand was built south of the Grandstand.

Yet in December 1865, the Race Committee elected “to erect a new Stewards’ Stand with private boxes, retiring rooms, and other accommodation, for the use of the stewards and other subscribers to the stand. The core of these buildings remain in service as what are now the Gimcrack Stand and the Press Room, just next door. The latter was constructed as a free-standing building, with the “Opera Boxes” (known internally as “Trumpers”) being an early twentieth century infill.

In 1907, the Committee embarked upon arguably its most dramatic phase of development. Having been tenants paying an annual rent on a year-by-year basis, in 1907 the racecourse was granted a 35-year lease.

With greater security and control came an opportunity to expand its premises northwards. This marked the launch of an extensive and transformative redevelopment scheme, and the extension of a fruitful relationship with architect Walter Brierley.

Brierley was Yorkshire’s most prominent architect. From 1907 to 1913, he presided over a series of improvement projects, which included extensions to the 1867 County Stand and the 1875 Press Stand, and new Stands to appeal to a broader customer base.

Perhaps the most significant changes, though, were those made to the paddock. Between 1907 and 1909, the property line of the north end of the racecourse was expanded, allowing the creation of a new boundary wall, entrance gates, bars and a replacement weighing room.

The new perimeter wall and adjoining structures were built in red brick, classically proportioned, the wall still forms the eastern boundary. A less well-known version is the similar wall that surrounds the quadrangles of horseboxes over at Stableside.

The action on the track was also developed at a pace; what is now the Yorkshire Cup began its storied history with an initial cancellation due to the General Strike of 1926. With the feature sprint that became The Group One Nunthorpe Stakes first run in the same decade.

As the Knavesmire had done its duty by being a Prisoner of War Camp rather than as arable fields, the track was in a position to host “the victory St Leger” of 1945.

Celebrating the first winner of the Derby after the conflict, the Dante Stakes joined the race roster in 1958, with the John Smith’s Cup being lifted for the first time in 1960. With the fillies not forgotten as the Lowther Stakes first ran in 1946.

Society’s growing leisure time bred new expectations at racecourses: more comfortable seating, more seats under cover, more food and beverage outlets. All this ‘more’ necessitated bigger buildings.

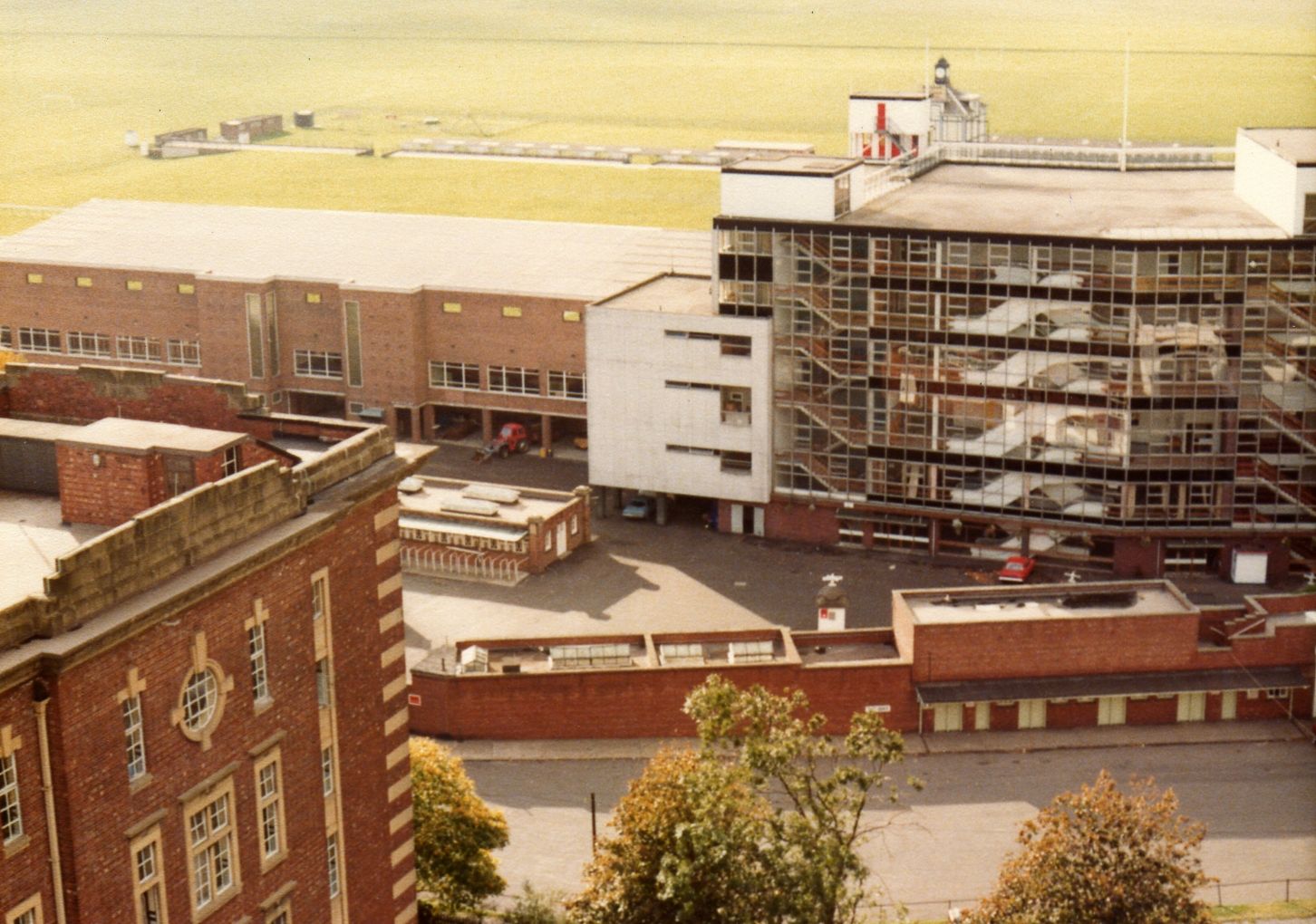

In 1957, a new stand was erected to the north of the Press Stand with a five-tier edifice simply known by the year of its construction, the 1965, was opened.

Come 1989, the 1957 stand was succeeded by the Melrose Stand (honouring a long serving Chairman) it remains in use with its red brickwork resonating with the staple of the Brierley era.

Seven years later in 1997, the Knavesmire Stand opened on the site of the 1959 stand.

Always open to high-profile visitors, some 250,000 pilgrims attended a Mass said by His Holiness Pope John Paul II in 1982.

For racing and Royal fans, 1972 was a significant year, the late Queen Elizabeth II was present to see Brigadier Gerard an upset favourite in the first running of the newest group One race at York, the Juddmonte International. The previous year had seen the start of another tradition at York, Macmillan Charity Raceday, an event that has already seen over £11million raised for good causes.

The new Millenium saw Sunday racing welcomed to York as the inaugural family raceday was staged that first September. By the middle of the decade, evening racing had been established, closely linked to the creation of Music Showcase Weekend that embraces headline performers of a different sort on the Knavesmire.

Completing the line-up of modern stands was the Ebor, five floors of contemporary space that have been open for racegoers to enjoy since May 2003.

It seemed almost every year brought an addition or upgrade to the Pattern race programme, five decades on from its debut as a handicap the 1895 Duke of York Sprint earned Group 2 stripes, The Silver Cup progressed as a July target for developing quality stayers, with the Strensall and Galtres amongst those promoted in the Ebor Festival schedule.

In every chapter of York’s history prize money has continued to increase, as have the facilities for connections and stable staff. The Owners & Trainers Club in the Melrose Stand was expanded towards the end of this decade.

A significant change to the track was made to facilitate the staging of Royal Ascot at York in 2005. The north bend was added to afford a complete circuit and permit the traditional distances for the Gold Cup and Queen Alexandra as famous contests. Though never formally designated a such, the Royal party made the Melrose Stand their home for five fabulous days.

The following year, the St Leger paid a second visit to York, keeping the oldest classic within the Broadacres.

Consistent down the centuries, the investments in prize money, as well as fixed facilities for connections & racegoers has continued in the last decade.

The richest race ever staged at York, the £1.25m Juddmonte International was recognised as the Best Race in the World in 2024, with the City of York Stakes upgraded to become the fourth Group One contest of the Sky Bet Ebor Festival.

Proud to be part of the wider community of York, there have been visits from both the Olympic Torch and the Paralympic Lantern, not to mention the start of the Grand Depart of the Tour de France in 2014.

The opening of the latest Weighing Room in 2015 was part of a development that relocated the Pre Parade Ring and was shortly followed by a major upgrade to the Stableside amenities for those looking after the star horses when away from home.

Racegoer facilities have improved on three points of the compass, the Clocktower Enclosure to the west seeing new pathways, toilets, and bar facilities with complete transformations of both the Northern and Southern (Bustardthorpe) Ends. The new facilities in these areas, opened in 2015 and then 2024 have found favour with racegoers and Awards Judges alike.

The Bustardthorpe End is recognised for its environmental sustainability, with a living roof, rainwater harvesting, solar panels and upcycled materials all forming part of the Green Knavesmire 300 initiative. This includes a pledge to be Nett Zero, less than a decade after the track celebrates its tercentenary in 1731; what better way to end a history than with such a strong look to the future.